USAIN BOLT didn’t build a monument — he rebuilt hope for his homeland, Jamaica.

The Caribbean sky turned black that September night. Hurricane Beryl, a monster Category 5 storm, tore across Jamaica in 2025 with winds that screamed at 180 mph. Roofs vanished. Rivers swallowed roads. In the parish of Trelawny, one building took the full fury.

Happy Hearts Children’s Home, shelter to 42 orphaned and abandoned kids, was flattened. Walls collapsed. The playground twisted into scrap metal. For days, the children slept under tarps while volunteers tried to salvage toys from the mud.

News reached Usain Bolt in Kingston the same morning. The fastest man ever alive dropped everything. He didn’t send a cheque. He didn’t post a sad emoji. He drove straight to the wreckage himself, still wearing slides and a training hoodie.

Residents recognised the 6-foot-5 figure picking through debris. Children who once cheered his Olympic golds now stood silent, barefoot in the rain. Bolt knelt, hugged the smallest girl, and promised something no one expected: “This place will come back better.”

Word spread fast. By evening, contractors who grew up idolising Bolt called offering help. Suppliers cancelled other jobs. Jamaicans overseas started GoFundMe pages titled “For Usain’s Kids.” Within 48 hours, donations crossed ten million Jamaican dollars.

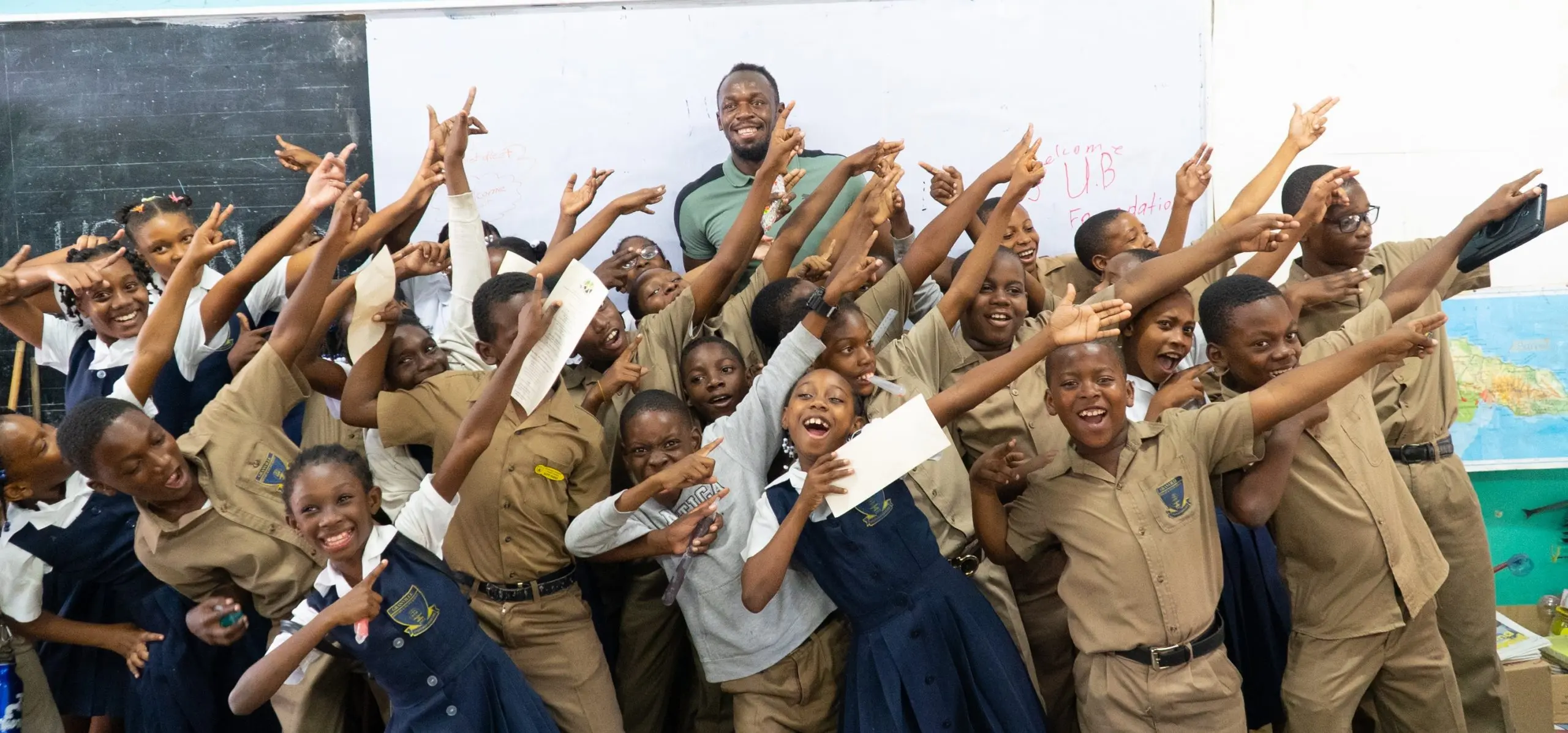

Bolt refused to be a distant hero. He set up a command tent on site. Every morning at six, he was there, moving blocks, directing engineers, joking with workers. The man who once circled tracks in 9.58 seconds now measured doorframes and checked rebar strength.

Six months of relentless work followed. The new Happy Hearts rose from concrete and hope. Solar panels now gleam on the roof. Hurricane-proof windows frame the Blue Mountains. Classrooms have smart boards. A therapy wing offers counselling the old building never had.

Cost: 175 million Jamaican dollars — roughly 1.1 million US dollars. Bolt covered every shortfall personally. He sold limited-edition spikes, auctioned race-worn bibs, and quietly moved money from his business accounts. Sponsors followed only after he had already committed half.

The dormitories carry soft colours chosen by the children. A mural of Bolt crossing an invisible finish line wraps the dining hall. Beneath his painted figure, the words read: “Start strong. Finish stronger. Live strongest.”

The dormitories carry soft colours chosen by the children. A mural of Bolt crossing an invisible finish line wraps the dining hall. Beneath his painted figure, the words read: “Start strong. Finish stronger. Live strongest.”

Opening day arrived under bright sunshine. The Governor-General cut the ribbon while children sang the national anthem with voices no longer afraid. Cameras flashed. Politicians lined up for photos. Bolt stood at the back, arms folded, eyes wet.

A local reporter pushed a microphone toward him. “Mr Bolt, you have everything — records, money, fame. Why do you do so much for these children?” The yard fell quiet. Even the breeze seemed to pause.

Bolt looked at the new building, then at the kids clutching new backpacks. His voice, usually playful, carried a weight no stadium had ever heard.

“I cannot stand by and watch my country fall,” he said. “These children are Jamaica’s next lap. If their start line is broken, I have to fix it. I run for them now.”

The silence that followed was deeper than any stadium roar. Mothers wiped tears. Construction workers who spent months beside him lowered their heads. A little boy ran forward and wrapped his arms around Bolt’s leg.

Social media carried the quote within minutes. #ICannotStandBy trended across the island. Taxi drivers played the clip on repeat. School principals read it in morning assembly. Jamaica, often bruised by hardship, felt something stronger than grief.

The facility is more than walls. It has a recording studio where teens produce reggae tracks. A sprint track circles the property — 80 metres, exactly the length Bolt ran before his famous 2008 Beijing lean. Every child learns to run there, barefoot or spiked.

Teachers say the children sleep better now. Nightmares about the storm have faded. When thunder rolls, they no longer hide under beds. They point to the reinforced roof and whisper, “Mr Bolt fixed it.”

Beyond Happy Hearts, the project sparked chain reactions. Corporate Jamaica launched a “Build Back Better” fund. Other parishes began upgrading vulnerable schools with the same storm-resistant designs. Bolt’s blueprint became national policy.

He still visits every Thursday. He brings jerk chicken, plays dominoes with the older boys, reads bedtime stories in that unmistakable deep voice. Staff say the children wait by the gate from noon, scanning every car for the familiar tall shadow.

Some critics once called him selfish, a showboat chasing endorsements. Those voices are quieter now. A man who could live anywhere chooses to pour wealth back into the red dirt that raised him.

On the wall of the new admin building hangs a simple plaque. No gold, no spotlight. Just words etched in steel:

On the wall of the new admin building hangs a simple plaque. No gold, no spotlight. Just words etched in steel:

“For the children who lost everything,

so they never lose hope again.

— Usain St. Leo Bolt”

Tourists now stop on the North Coast road to take photos of the colourful compound shining against green hills. Locals correct them gently: “That’s not a monument. That’s Jamaica standing back up.”

And somewhere inside, a little girl who once cried under a tarp now lines up on the 80-metre track. She crouches into her blocks, looks at the mural of her hero, and whispers the line she has memorised.

“I cannot stand by and watch my country fall.”

Then she explodes forward, legs churning, carrying the fastest hope Jamaica has ever known.