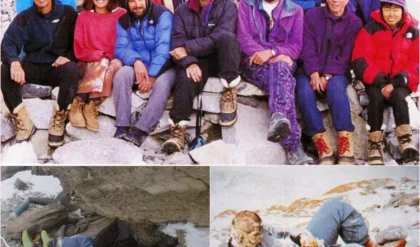

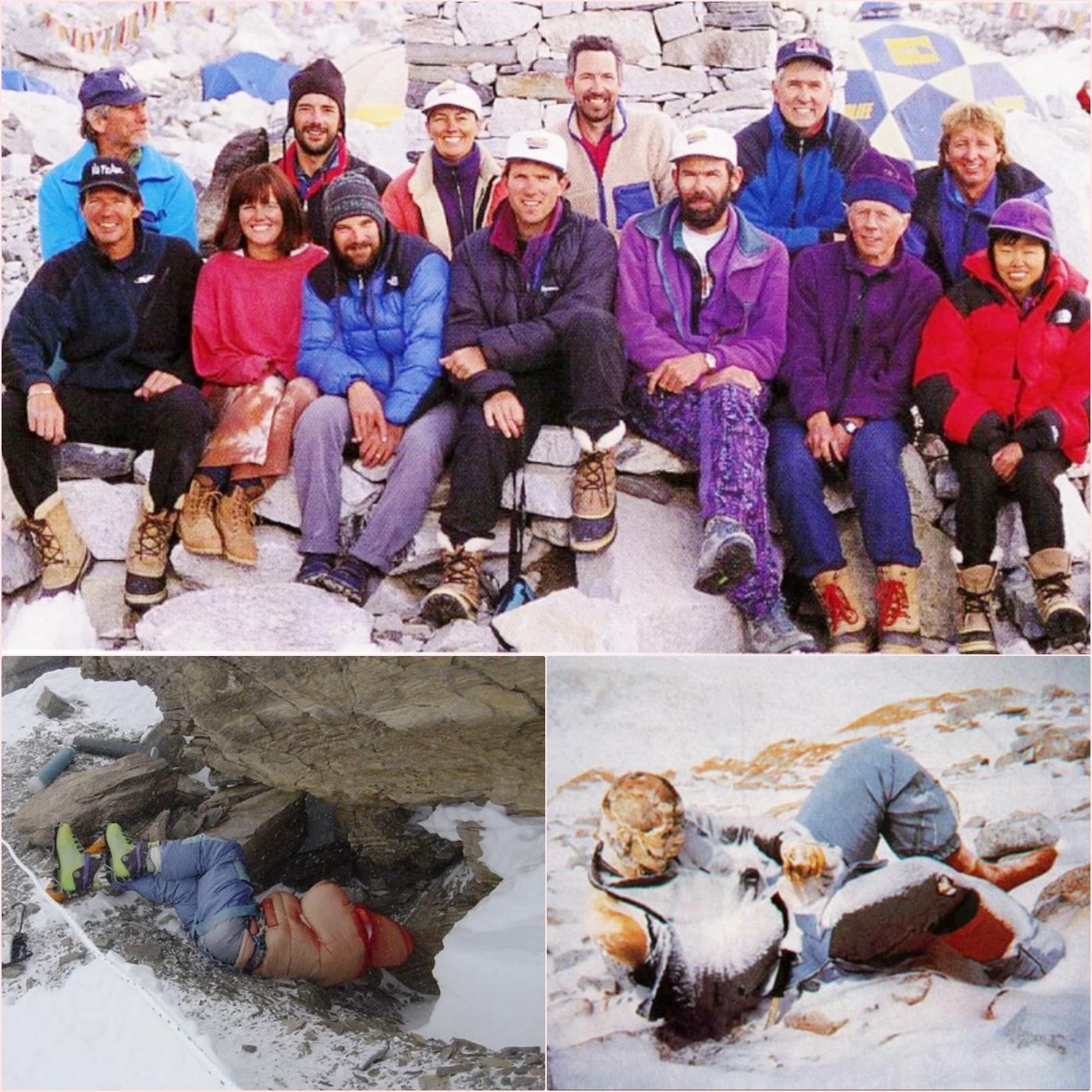

On the icy slopes of Everest, the “death zone” above 8,000 meters (26,000 feet) hides a tragic reality: more than 200 climbers’ bodies lie frozen in the snow and ice, impossible to repatriate. This phenomenon, both macabre and fascinating, is explained by physical, logistical, and ethical constraints that make the repatriation of these remains almost impossible.

In the death zone, the thin air contains barely a third of the oxygen available at sea level. Every step becomes a challenge, every effort a mortal risk. Often exhausted, climbers succumb to hypoxia, extreme cold, or avalanches. Recovering a body in these conditions is a Herculean task. The weight of a body, combined with the equipment needed to transport it, can exceed 100 kilos. Sherpas and rescuers, already at the limit of their physical capabilities, risk their own lives for such a mission. A recovery operation can require days, large teams, and considerable resources, often at the expense of everyone’s safety.

Unpredictable weather conditions exacerbate the situation. Sudden storms, strong winds, and temperatures that can drop below -40°C make rescue operations perilous. Moreover, the steep terrain, with its crevasses and steep slopes, complicates any movement. Some bodies, such as that of “Green Boots,” a climber who died in 1996, have become gruesome landmarks for climbers, integrated into the mountain’s hostile landscape.

Financial considerations also play a role. An expedition to Everest costs tens of thousands of dollars, and a recovery mission can double that amount. Families, often grieving, do not always have the means to finance such an undertaking. The Nepalese and Chinese governments, which control access to Everest, do not offer systematic logistical support for these operations, leaving families facing a cruel dilemma: abandon their loved one or risk other lives.

On the icy slopes of Everest, the “death zone,” above 8,000 meters, hides a tragic reality: more than 200 climbers’ bodies lie frozen in the snow and ice, impossible to repatriate. This phenomenon, both macabre and fascinating, is explained by physical, logistical, and ethical constraints that make repatriating these remains almost impossible.

In the death zone, the thin air contains barely a third of the oxygen available at sea level. Every step becomes a challenge, every effort a mortal risk. The climbers, often exhausted, succumb to hypoxia, extreme cold, or avalanches. Recovering a body in these conditions is a Herculean task. The weight of a body, combined with the equipment needed to transport it, can exceed 100 kilos. Sherpas and rescuers, already stretched to their limits, risk their lives for such a mission. A recovery operation can require days, large teams, and considerable resources, often at the expense of everyone’s safety.

Unpredictable weather conditions exacerbate the situation. Sudden storms, strong winds, and temperatures that can drop below -40°C make rescue operations perilous. Moreover, the steep terrain, with its crevasses and steep slopes, complicates any movement. Some bodies, such as that of “Green Boots,” a climber who died in 1996, have become macabre landmarks for climbers, integrated into the mountain’s hostile landscape.

Financial considerations also play a role. An expedition to Everest costs tens of thousands of dollars, and a recovery mission can double that amount. Families, often grieving, do not always have the means to finance such an undertaking. The Nepalese and Chinese governments, which control access to Everest, do not offer systematic logistical support for these operations, leaving families facing a cruel dilemma: abandon their loved one or risk other lives.

Ethically, the issue is divisive. Some believe that leaving the bodies behind is disrespectful, while others, including many climbers, view Everest as a sanctuary where the deceased rest in their final conquest. Deeply spiritual Sherpas sometimes believe that disturbing the dead could offend the mountain’s deities.

Finally, the ice preserves these bodies as relics, slowing their decomposition. They remain visible, sometimes for decades, a reminder of human fragility in the face of nature. Recovering them would erase part of Everest’s history, an involuntary memorial to those who dared to challenge its summits.

Thus, the bodies of Everest remain in the death zone, not out of indifference, but because of a complex mix of dangers, costs, and beliefs. They embody the ultimate price of human ambition in the face of an unforgiving mountain.

Ethically, the issue divides opinion. Some believe that leaving the bodies there is disrespectful, while others, including many climbers, view Everest as a sanctuary where the deceased rest in their final conquest. Deeply spiritual Sherpas sometimes believe that disturbing the dead could offend the mountain’s deities.

Finally, the ice preserves these bodies as relics, slowing their decomposition. They remain visible, sometimes for decades, a reminder of human fragility in the face of nature. Recovering them would erase part of Everest’s history, an involuntary memorial to those who dared to challenge its peaks.

Thus, the bodies of Everest remain in the death zone, not out of indifference, but because of a complex mix of dangers, costs, and beliefs. They embody the ultimate price of human ambition in the face of an unforgiving mountain.