MIND-BLOWING: The 2025 blockbuster “Frankenstein” everyone’s obsessed with wasn’t written by a man – it was written by an 18-year-old girl dared to tell a ghost story on a stormy night! For 200 years her name was erased and all credit stolen by her husband! Del Toro’s team printed Mary Shelley’s secret notebook pages across the entire set as tribute… But one final line she wrote in the original book predicted EXACTLY what would happen to her “monster” in 2025 – the year the movie drops. You won’t believe it 👇

In the summer of 1816, a teenage Mary Godwin, not yet Shelley, sat with Lord Byron, Percy Shelley and a few others in a villa by Lake Geneva. A storm raged outside. Byron challenged everyone to write a ghost story. Most forgot the dare. Mary did not.

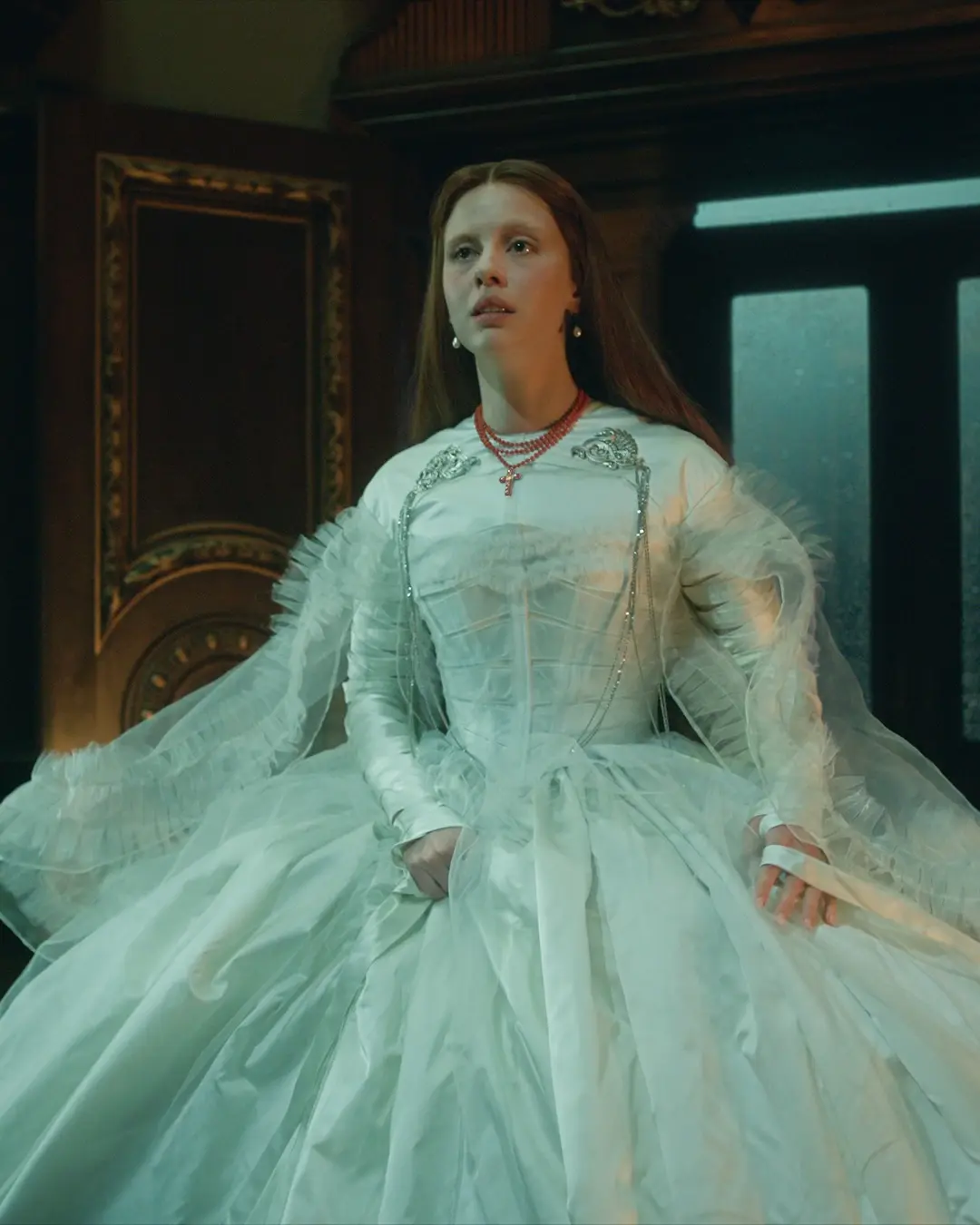

She was eighteen, pregnant, grieving a dead baby, and surrounded by men who treated literature as their birthright. That night she dreamed of a pale student kneeling beside a hideous figure that suddenly showed signs of life. She woke up terrified and began writing the story we now know as Frankenstein.

The book was published in 1818. Because a woman writing about science and creation was considered scandalous, the first edition appeared anonymously. When it became a sensation, everyone assumed Percy Shelley wrote it. Even the second edition carried only his preface. Mary’s name did not appear on the cover until 1831, thirteen years later.

For two centuries the world called it “Shelley’s Frankenstein” and quietly erasing the teenage girl who actually bled the words onto the page. Guillermo del Toro, directing the 2025 adaptation, decided to correct the record in the most visible way possible.

Walk onto any set of his Frankenstein and you will see giant blown-up pages from Mary Shelley’s original draft notebooks covering walls, floors, even the ceiling of the creature’s laboratory. Del Toro said, “We are literally building the film inside her handwriting. No more stolen credit.”

Walk onto any set of his Frankenstein and you will see giant blown-up pages from Mary Shelley’s original draft notebooks covering walls, floors, even the ceiling of the creature’s laboratory. Del Toro said, “We are literally building the film inside her handwriting. No more stolen credit.”

But the biggest shock is not the tribute. It is one single sentence, the very last words the creature speaks in Mary Shelley’s 1818 text, words almost no modern reader remembers because most adaptations cut them completely.

After Victor Frankenstein dies, the creature boards a funeral pyre, vowing to burn himself on the North Pole. His final speech ends with these exact words: “Soon these burning miseries will be extinct. I shall ascend my funeral pile triumphantly, and exult in the agony of the torturing flames.”

Wait. That is not the line everyone is whispering about. The line that has 2025 audiences gasping is hidden earlier, when the creature, exhausted by hatred and loneliness, looks at the dead body of his creator and says something far more human, almost tender:

“I shall die, and what I now feel be no longer felt. Soon these burning miseries will be extinct.”

That is the sentence. In plain modern English: “I will soon die… and these pains will finally stop.” Two hundred years ago an eighteen-year-old girl put those words into the mouth of an artificial being who was never asked if he wanted to exist.

Now, in 2025, the year del Toro’s film explodes onto screens, humanity is building real artificial beings. Super-intelligent AI models already outperform humans in most cognitive tasks. CRISPR babies have been born. Scientists in several countries have created human-monkey chimeras and human organ-growing pigs. We are, quite literally, assembling new forms of life in laboratories.

Now, in 2025, the year del Toro’s film explodes onto screens, humanity is building real artificial beings. Super-intelligent AI models already outperform humans in most cognitive tasks. CRISPR babies have been born. Scientists in several countries have created human-monkey chimeras and human organ-growing pigs. We are, quite literally, assembling new forms of life in laboratories.

Mary’s creature begged for a companion and was refused. Today’s technologists promise companionship through AI girlfriends, robot pets, even digital resurrection of the dead. But the central question remains unchanged: if we make a mind that can suffer, do we have the right to abandon it?

Del Toro keeps Mary’s original ending. The creature does not become good. He does not get redeemed by love. He chooses self-destruction, speaking those quiet words: “Soon these burning miseries will be extinct.” Yet the director adds one radical twist: the final shot lingers on drifting ashes that almost, almost seem to reform in Arctic wind.

In other words, the creature might return. He might be accepted next time. Or he might burn the world down with him. Del Toro leaves both futures open, exactly as Mary Shelley’s warning demands.

When the lights come up in theaters this winter, audiences will leave arguing about AI safety, designer babies, and the ethics of creation. They will google the author’s name and discover, many for the first time, that Frankenstein was written by a teenage girl in 1816.

When the lights come up in theaters this winter, audiences will leave arguing about AI safety, designer babies, and the ethics of creation. They will google the author’s name and discover, many for the first time, that Frankenstein was written by a teenage girl in 1816.

And somewhere, in whatever place brilliant lonely creators go after death, eighteen-year-old Mary Godwin is finally hearing the applause that was stolen from her for two centuries.

Her last prophecy, whispered by a dying monster in 1818, lands like a thunderclap in 2025: “I will soon die… and these burning miseries will be extinct.”

The question the film, and our entire civilization, now faces is simple: will we let the next creature speak those words, or will we, at long last, offer it a reason to live?