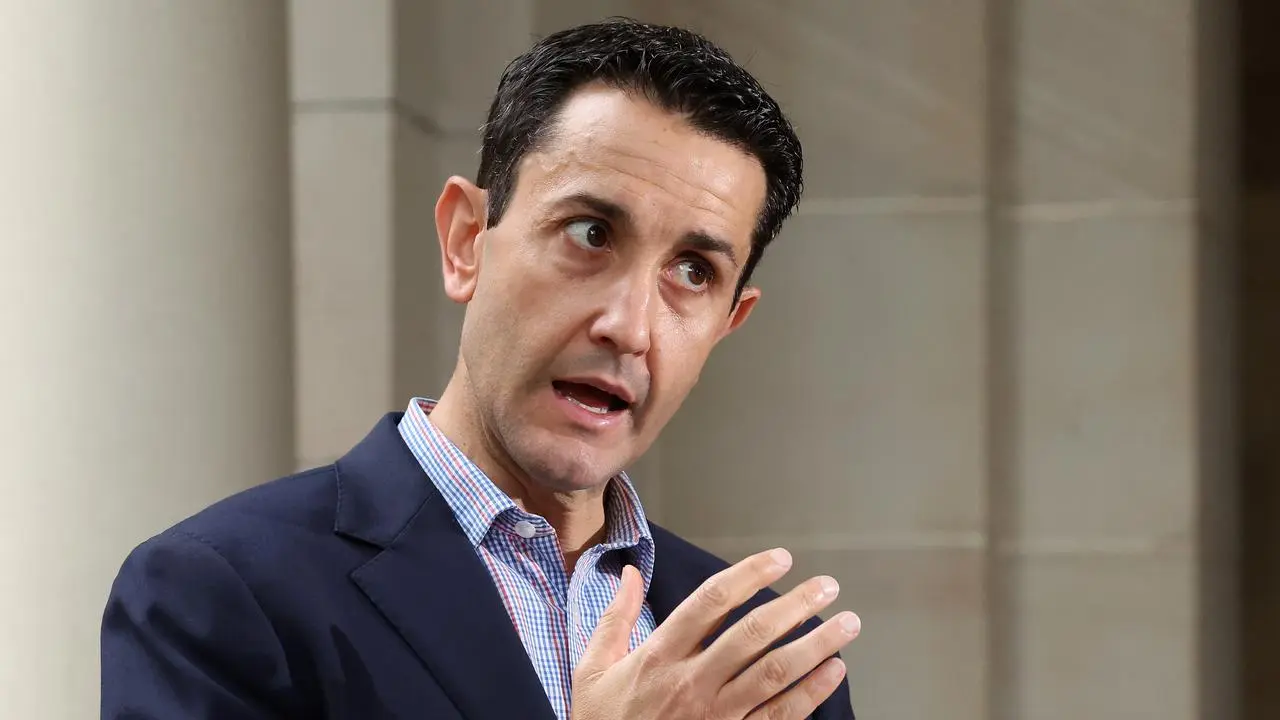

The political temperature in Australia spiked sharply after Queensland Premier David Crisafulli delivered a blunt rejection of Canberra’s proposed gun buyback scheme, sending shockwaves through federal politics and placing Prime Minister Anthony Albanese under intense national scrutiny.

Crisafulli’s declaration was not carefully hedged language. It was direct, confrontational, and unmistakably political. By refusing participation, Queensland signaled that the federal government’s authority on firearms reform would no longer go unchallenged by the states.

Labeling the proposal a “gun buyback farce,” Crisafulli framed the policy as disconnected from rural reality. His words resonated deeply across regional Queensland, where firearms are often viewed as tools of livelihood rather than symbols of violence.

The Premier accused Canberra of governing from a distance, arguing that urban policymakers fail to understand rural communities. He suggested the scheme unfairly burdens farmers, hunters, and ranchers who comply with existing laws and use firearms responsibly.

Central to Crisafulli’s argument was cost-sharing. He rejected the idea that Queensland taxpayers should help fund a federal initiative he views as misguided, expensive, and politically motivated rather than evidence-based.

By invoking Bondi and other recent incidents, Crisafulli shifted blame away from legal gun owners. He argued that failures in policing, intelligence, and early intervention were being ignored in favor of symbolic legislative responses.

This reframing struck a chord among critics of the buyback plan, who argue that sweeping reforms risk punishing compliance while failing to address root causes of violence, including mental health gaps and enforcement shortcomings.

The federal government, meanwhile, insists the reforms are necessary and overdue. Albanese has repeatedly described the proposal as the most significant gun policy overhaul in three decades, aimed at preventing future tragedies.

Queensland’s refusal threatens that narrative. When a state with vast rural populations rejects cooperation, the image of national consensus fractures, exposing the limits of federal persuasion in Australia’s federated system.

Crisafulli’s stance immediately aligned Queensland with Tasmania and the Northern Territory. Together, they form what commentators are calling a growing coalition of resistance, challenging Canberra’s authority and strategic cohesion.

This alliance is less about ideology than identity. Each jurisdiction has significant regional populations that view gun ownership through cultural, occupational, and historical lenses distinct from metropolitan perspectives.

For Albanese, the challenge is no longer purely legislative. It is political and symbolic. A reform touted as national now appears contested, raising doubts about whether federal leadership can unify states behind difficult policy choices.

Opposition figures seized on the moment, framing the resistance as proof that Canberra is out of touch. They argue that the Prime Minister underestimated state pushback and overestimated public appetite for centralized control.

Supporters of the buyback counter that leadership requires firmness, especially on public safety. They warn that fragmentation undermines national standards and risks creating regulatory loopholes across state borders.

The dispute has reignited debate over federalism itself. How much authority should Canberra wield in areas traditionally managed by states? Gun policy, once settled after past reforms, is again testing that balance.

Crisafulli’s rhetoric emphasized dignity and autonomy. By portraying rural Australians as unfairly targeted, he positioned himself as a defender of communities that feel politically invisible in national debates.

That framing has electoral implications. Regional voters often feel sidelined, and Crisafulli’s resistance may strengthen his standing at home while complicating Albanese’s outreach beyond major cities.

Inside Canberra, concern is growing. Officials fear that further state defections could stall implementation entirely, forcing the federal government to dilute, delay, or renegotiate key elements of the reform package.

The language of “biggest reforms in 30 years” now carries risk. Ambition invites judgment, and failure to deliver unified action could redefine the policy as overreach rather than progress.

Policy analysts note that gun reform in Australia has historically relied on cooperation rather than coercion. Without state buy-in, enforcement and funding mechanisms become legally and politically fragile.

Public opinion remains divided. Urban voters largely support tighter controls, while rural communities express frustration at being blamed for violence they believe they did not cause.

Media coverage has amplified the clash, framing it as a power struggle between Canberra elites and state leaders claiming to represent everyday Australians outside metropolitan centers.

Albanese has so far avoided direct confrontation, emphasizing dialogue and national interest. Yet silence risks being interpreted as weakness at a moment when authority is openly challenged.

Crisafulli, by contrast, appears energized by the conflict. His remarks suggest a willingness to escalate, framing the dispute as a matter of principle rather than negotiation.

The federal government faces a narrowing window. Either it recalibrates the policy to accommodate dissenting states, or it risks presiding over a reform that exists more on paper than in practice.

Some experts warn that prolonged conflict could erode trust between governments, complicating cooperation in other critical areas such as health, disaster response, and infrastructure funding.

Others argue the confrontation is healthy. They see it as democratic friction, forcing better policy design through debate rather than rubber-stamp consensus.

What is clear is that the gun buyback plan has become more than legislation. It is now a test of leadership, federal authority, and political credibility.

Queensland’s refusal has emboldened skeptics nationwide, encouraging other states to reassess their positions quietly, if not publicly.

Albanese’s reform agenda now faces its most serious obstacle. The question is no longer whether the policy is bold, but whether it is governable.

As Canberra and the states dig in, compromise appears distant. Each side frames the issue as protecting Australians, yet they define that protection in fundamentally different ways.

The coming months will determine whether this coalition of resistance grows or fractures, and whether federal resolve hardens or bends under pressure.

For now, the power struggle remains unresolved. What began as a policy announcement has evolved into a defining confrontation over who truly speaks for Australia’s diverse communities.

In that tension lies the future of the reform, and perhaps a broader reckoning over how national leadership functions in a country shaped as much by distance as by democracy.