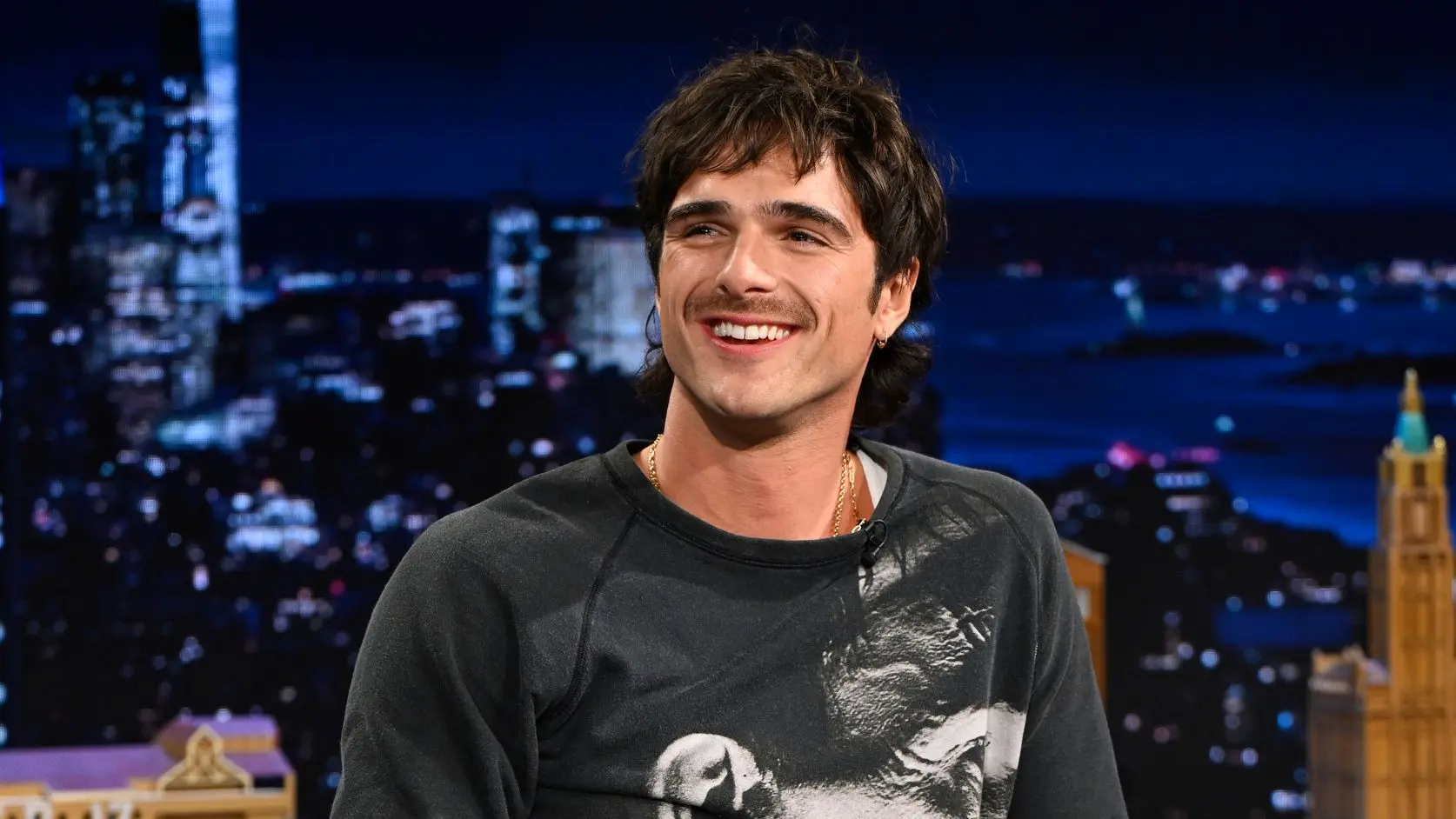

Jacob Elordi reveals a shocking “magical” secret on the set of Frankenstein: The makeup didn’t just transform his appearance—it awakened a deep emotion that nearly brought him to tears! You won’t believe what happened behind the scenes… Read the full story below 👇

The first time Jacob Elordi saw himself fully transformed into Guillermo del Toro’s Creature, something unexpected happened. He was alone in the makeup trailer at 4 a.m., surrounded by mirrors and silence. The prosthetics were still wet, the neck bolts cold against his skin.

He had expected to feel monstrous. Instead, he felt recognised. The heavy brow, the scarred flesh, the stitches across his cheek—everything the world would later call terrifying looked, in that moment, heartbreakingly vulnerable. His own eyes stared back, wide and lost.

Jacob stood frozen for nearly ten minutes. The makeup team had stepped out to give him space. When the lead artist returned, she found the 6’5” actor trembling. Not from fear of the reflection, but from something far deeper.

Later that day, during a quiet lunch break, Jacob pulled Guillermo aside. His voice was barely above a whisper. “I think I just met him,” he said. “Not the monster. The child who never got held.” Del Toro only nodded—he had been waiting for this exact moment.

The director had warned the crew: the makeup was never just about horror. Every scar, every asymmetry, every exposed stitch was designed to force empathy. “We’re not making a villain,” del Toro kept repeating. “We’re making the most misunderstood baby in literature.”

For weeks, Jacob had intellectually understood the assignment. He had read Mary Shelley until the pages frayed. He had studied loneliness like a second language. But intellect is not the same as recognition, and recognition, he discovered, can break you open.

For weeks, Jacob had intellectually understood the assignment. He had read Mary Shelley until the pages frayed. He had studied loneliness like a second language. But intellect is not the same as recognition, and recognition, he discovered, can break you open.

The turning point came on a rainy night shoot in the forest. Jacob, in full Creature makeup and costume, was supposed to collapse after being chased by torch-wielding villagers. It was take seventeen. Everyone was exhausted.

As he fell to his knees in the mud, something inside him cracked wide open. The weight of the prosthetics suddenly felt like centuries of rejection pressing down on his chest. He couldn’t breathe. Not from the makeup—this was different.

Tears came without warning. Not actor tears, not glycerin drops. Real, hot, uncontrollable tears that ran down the silicone scars and pooled inside the neck bolts. Jacob tried to hide them, ashamed, but the camera was already rolling.

Guillermo didn’t call cut. He let the camera keep turning. Twenty seconds. Thirty. A full minute of Jacob sobbing silently on his knees while rain mixed with tears and makeup blood. The sound recordist later said it was the most devastating thing he’d ever captured.

When del Toro finally yelled “Cut,” the set was eerily quiet. No one moved. Jacob stayed on the ground, shoulders shaking. Then, slowly, crew members began to cry too. The gaffer. The script supervisor. Even the security guard who never spoke.

Jacob later described it as the moment the Creature stopped being a role and started being a person living inside his body. “I felt his entire life at once,” he said. “Every time he reached out and no one reached back. I understood him so completely it hurt.”

That take is not in the final film—too raw, too exposed—but del Toro kept the footage. He plays it for actors during prep now, calling it “the soul of the movie.” Jacob calls it the day he stopped acting and started mourning.

After that night, everything changed. Jacob refused to remove certain pieces of makeup between takes. He wanted to stay inside the Creature’s skin as long as possible. “If I take it off,” he told the makeup team, “I might not find my way back to him.”

After that night, everything changed. Jacob refused to remove certain pieces of makeup between takes. He wanted to stay inside the Creature’s skin as long as possible. “If I take it off,” he told the makeup team, “I might not find my way back to him.”

There were days when he wouldn’t speak in his own voice at all. He communicated only in the Creature’s broken grunts and gestures. The crew adapted, learning to read his eyes through layers of latex and pain.

One afternoon, a young extra—a teenager with visible burn scars—approached Jacob during a break. The boy was nervous, starstruck. Jacob, still in full monster makeup, knelt so they were eye level. Without words, he gently touched the boy’s scarred cheek, then his own.

The teenager burst into tears. Jacob pulled him into a hug that lasted minutes. When they finally let go, the boy whispered, “Thank you for making him beautiful.” Jacob couldn’t speak—he just nodded, tears falling again beneath the prosthetics.

That moment never made tabloids. No phones were out. It belonged only to the two of them and the rain-soaked forest. But everyone on set felt the shift: the Creature was no longer fiction. He was real, and he was loved.

Months later, at the film’s first test screening, something remarkable happened. During the Creature’s most tragic scene, the audience didn’t gasp in terror—they wept. Grown men openly sobbed. Children hid not from fear, but from the unbearable weight of empathy.

Months later, at the film’s first test screening, something remarkable happened. During the Creature’s most tragic scene, the audience didn’t gasp in terror—they wept. Grown men openly sobbed. Children hid not from fear, but from the unbearable weight of empathy.

Jacob sat in the back row, watching strangers cry for the monster he had carried inside his own skin. When the lights came up, he was crying too. Not from pride, but from relief. The Creature had finally been seen.

In interviews now, Jacob is protective of that moment in the makeup trailer. “People want to hear about the eight-hour makeup process or the physical transformation,” he says. “But the real magic wasn’t what they put on my face. It was what my face finally let me feel.”

He still has the neck bolts. They sit in a glass case in his apartment—not as trophies, but as reminders. Some nights, when the loneliness feels too familiar, he takes one out and holds it. The cold metal against his palm brings back the exact weight of that first recognition.

Because once you’ve cried with a monster’s eyes, something in you stays broken open forever. And for Jacob Elordi, that crack is where the light—and all the real acting—comes in.