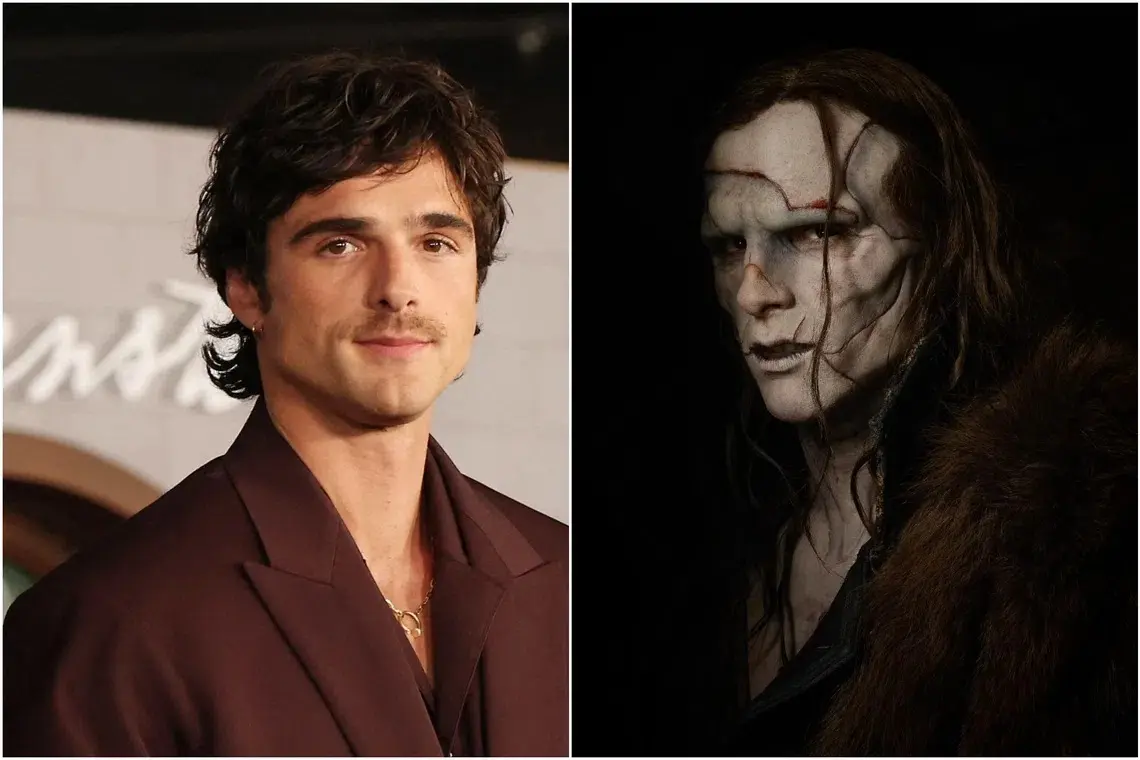

Jacob Elordi stuns audiences with a performance hailed as the ‘peak of his career,’ transforming into a creature both heartbreaking and deeply human in a ‘snow-drenched gothic opera.’

Del Toro reveals he chose Elordi based on just one thing… his eyes. But the biggest surprise lies in a childhood inspiration Elordi has never shared with anyone…

The Sala Grande at Venice had never been so quiet. When the screen finally went black after 162 minutes, the silence stretched to eight seconds, then ten. Then the dam broke. People stood, screamed, cried. Some simply stayed seated, staring at the credits as if the creature might crawl back out.

Guillermo del Toro’s untitled new film (already nicknamed “the Carpathian requiem” or “the snow-drenched gothic opera”) is not just a movie. It is a possession. And Jacob Elordi, buried under seven hours of daily prosthetics, is the one possessed.

He plays an immortal being abandoned in the 14th century inside a frozen monastery high in the Carpathians. Half man, half fallen angel, half beast (del Toro refuses to choose), the creature has survived on prayer, blood, and memory for seven hundred years. Until one winter night, a lost child stumbles through the snow…

Critics have run out of superlatives. The Guardian: “Elordi delivers the single greatest creature performance since Andy Serkis redefined the form.” IndieWire: “He makes you forget prosthetics exist.” Screendaily’s verdict was one line: “This is the role actors dream of when they are eight years old and hiding under the blanket with a torch and a DVD of The Fellowship of the Ring.”

Because that is exactly where it started.

On the red carpet, soaked by Venetian rain, Elordi finally told the story no one knew. When he was eight, living in Brisbane, his cousin locked him in a room and forced him to watch The Two Towers. The scene that destroyed him was Gollum in the Dead Marshes, whispering “My Precious” while tears froze on his face.

“I paused the DVD fifty times,” Elordi said, voice cracking. “I kept going frame by frame on Gollum’s eyes. I thought: how can something that ugly make me cry this much? That night I decided that one day I would be the monster people couldn’t stop loving.”

He never told a soul. Not his drama teacher. Not his agents. Not even his mother. For nineteen years he carried that eight-year-old’s dream in silence.

Then, in March 2024, an email arrived from Guillermo del Toro. Subject line: “For the boy who loved Gollum.” Attached was a 180-page script and one handwritten note: “Page 42. Read it and call me.”

Page 42 was the creature’s first close-up: a single tear freezing halfway down a ruined cheek. In the margin del Toro had written: “Think of the Dead Marshes, but colder. Think of the child you were.”

Elordi called from his kitchen floor, crying so hard he could barely speak. “Yes,” was all he managed. Del Toro replied, “Good. Bring the child with you.”

Elordi called from his kitchen floor, crying so hard he could barely speak. “Yes,” was all he managed. Del Toro replied, “Good. Bring the child with you.”

Shooting took place in the Rhodope Mountains of Bulgaria at minus 25 °C. Elordi refused the heated trailer. He stayed outside between takes, letting ice form on the silicone scars so the creature would never feel warm.

Every morning the make-up team spent four hours gluing hand-punched silver hairs one by one. Then three more hours building ice crystals on his eyelids so he could barely blink. When they asked if it hurt, he only said, “Gollum never got to be warm either.”

The voice is another miracle. Elordi created it himself: a mix of whispered Latin prayers, guttural Old Church Slavonic, and the broken English of someone who hasn’t spoken to another soul in centuries. Del Toro claims he never gave a single note on the voice. “It arrived fully formed from whatever cave that eight-year-old boy had been hiding in.”

There is one scene the festival cannot stop talking about. The creature finds an abandoned chapel. He lights a candle with shaking claws. He tries to remember how to pray. He fails. So he simply whispers the word “please” in eleven dead languages, ninety seconds without a cut, eyes filling with tears that freeze before they fall.

Half the theatre sobbed so loudly the sound mix was drowned out.

After the screening del Toro took the microphone, eyes wet. “I have made many monsters. This one is different. This one is Jacob’s childhood come alive. I just gave him permission to let the eight-year-old take over.”

Elordi joined him on stage still wearing remnants of silver paint around his eyes. He could barely speak. “For twenty years I was ashamed of loving a creature more than any prince. Tonight you made me feel like the luckiest boy in the world.”

Elordi joined him on stage still wearing remnants of silver paint around his eyes. He could barely speak. “For twenty years I was ashamed of loving a creature more than any prince. Tonight you made me feel like the luckiest boy in the world.”

Then he turned to the director and said the line that is already printed on T-shirts outside the Lido: “Thank you for letting me be the monster I always wanted to be when I was eight.”

The ovation lasted fourteen minutes. People refused to leave. Some knelt in the aisle as if they had witnessed a miracle.

As he walked off stage, a journalist shouted: “Will you ever play human again?” Elordi paused, those ancient eyes shining under the spotlights, and answered with a smile that belonged to both the man and the child:

“If the creature lets me go.”

He won’t. And nobody wants him to.